Art by Clark Miller

Art by Clark MillerFame, Feud and Fortune: Inside Billionaire Alexandr Wang’s Relentless Rise in Silicon Valley

The Scale AI co-founder has turned AI grunt work into a thriving business while hotly pursuing a place among the tech elite.

In January 2021, Alexandr Wang’s friends and colleagues gathered for a party at his swank South of Market apartment, which featured a 2,000-foot private terrace with a hot tub and views of the San Francisco skyline. Wang, co-founder and CEO of Scale AI, wanted to mark his birthday with a bang: He was turning 24.

Wang had spent the holidays with his family in his native New Mexico and returned to San Francisco to celebrate with the clan he had formed in the city, many of whom belonged to Silicon Valley’s most elite circles. The party’s attendees included Sam Altman, OpenAI’s CEO and co-founder, who lived with Wang at the apartment for several months during the pandemic. While others were reveling, Altman sat at his desk working for a portion of the party, one attendee recalled.

In the years since, Wang, who declined to comment for this story, has further cemented himself in the upper echelons of Silicon Valley, partly through his knack for getting into the right rooms and securing the high-powered connections that can propel a young founder’s fortunes.

His climb underscores how interwoven those ties can become: OpenAI, for example, is an important customer of Scale, which supplies AI companies with contract workers to fine-tune their data. Last fall, Altman and Wang actually discussed the prospect of OpenAI buying Scale, according to a person informed about the talks, though the deal never reached a formal stage.

Instead, Wang kept Scale independent and raised $1 billion over the course of several months, with Scale at a $13.8 billion valuation. Thanks partly to Scale’s deals with OpenAI, revenue is booming, and Scale has forecast more than $1 billion in sales this year, catapulting it to the top ranks of generative AI companies by sales.

For the most part, those sales come from what amounts to AI grunt work: Scale employs a vast but relatively low-paid workforce to label and train the data that underpin the AI systems developed by Scale’s customers, including OpenAI, Meta Platforms and Alphabet. They rely on Scale contractors to push their AI products toward creating more human-like responses; the contractors teach the AI by writing their own responses to questions submitted to chatbots.

Over the past eight years, Wang has successfully steered Scale in whatever direction AI was leaning. In the process, he has proven himself a crafty opportunist, shifting Scale toward fresh pools of revenue when old ones dried up. His nimbleness comes from considerable careful study.

“I don’t think he figured out where the world is going by sitting in his bedroom and thinking about it. He spends time with the right people. He gathers a lot of data on where the world is going and can reorient the business around it,” one Scale investor told me.

Wang has also become a polarizing figure in Silicon Valley, as my conversations with more than 30 people who know him make apparent. At times, he has overpromised investors and customers about Scale’s potential, and according to some people who have worked with him, he’s a controlling boss.

For example, even though mutual funds now commonly invest in tech startups, Wang wouldn’t allow any such funds to invest in Scale’s latest round, since they would eventually publicly disclose their private valuations of the startup—information that could embarrass Wang if the numbers began to decline. Internally, Wang has frustrated some staff with his need to approve every hire, even as the company has grown past 800 full-time employees.

Part of his polarizing reputation also comes from the fact that Wang holds grudges. Unhappy with high staff turnover amid intense industrywide competition for AI workers, he has prevented ex-employees from selling shares in an upcoming secondary offering—forcing them to continue waiting to sell their illiquid stock.

Wang also has complained privately that Scale’s rising valuation has made his spurned co-founder, Lucy Guo, much wealthier thanks to the hundreds of millions of dollars of Scale shares she still holds. (A Scale spokesperson denied Wang said this.)

Wang, now 27, is likely to have a long career ahead of him. The tech titans who seem like they have been around Silicon Valley forever were barely getting started at that age. Elon Musk wasn’t yet working at PayPal, Marc Andreessen hadn’t sold Netscape to AOL, Vinod Khosla hadn’t even started Sun Microsystems and Altman wasn’t yet president of Y Combinator.

When I discussed Wang and his relentless scramble to the top of Silicon Valley with a fellow founder who knows him well, the founder described Wang as someone who “needed success like he needed oxygen.”

Wang certainly isn’t shy about expressing his ambition. In an internal Scale database that includes employees’ profiles and icebreaker questions for people to ask their colleagues, Wang has written: “Ask me how to turn Scale into a $100 billion company.”

To the public, Wang presents a curated version of his world and life, one that shows him embracing celebrity and social access.

On his publicly accessible Instagram, he has nearly a million followers. Over roughly the past year, Wang treated his audience to mirror selfies from the Met Gala; photos with famous friends such as actor Kiernan Shipka; and candid shots with the young, rich and famous in tech, including Altman, Brex co-founder Henrique Dubugras and Figma founder Dylan Field. (Don’t bother looking for the photos—Wang recently appeared to set many of them to private.)

When Wang commented on X earlier this year that he had spent the past several years “traveling like crazy,” Altman teased him publicly over the comment. “Truly no one flies in and out to more parties than you,” Altman wrote on X, “it looks like a full time job.”

Inside Scale, employees like to gossip about which startup-investor celebrities Wang is meeting with, a group that has included Orlando Bloom and Jared Leto. His profile rose with a blaring 2022 Forbes headline that heralded him as the world’s youngest self-made billionaire. “Internally, it was, ‘He’s a rock star—he’s our rock star,’” said John Matthews, Scale’s former head of international expansion.

Wang is constantly in motion. In recent months, he has appeared onstage with U.S. army generals in Washington (Scale generates more than $100 million in annual revenue from government contracts) and behind closed doors with government officials in Qatar to pitch Scale’s services. (Qatar, like other countries, has been interested in developing its own large-language models and AI infrastructure.) And in March, Wang hobnobbed at a private conference at the Yellowstone Club ski resort in Montana with Altman, Google billionaire Eric Schmidt and star talent agent Ari Emmanuel.

While he is often one of the youngest in these rooms, Wang sometimes likes to spar with more seasoned tech figures. At the Yellowstone Club, Wang stood up during an AI panel to push back against another speaker, Databricks CEO Ali Ghodsi, who said it would be years before AI models could store an infinite amount of knowledge—a delay that wouldn’t be good for Scale’s customers. No, Wang said, that day was coming soon.

Still, Wang mostly relies more on charm than combativeness. “The first time I met Alex was at a wild dinner in Las Vegas,” recalled Sen. Mark Warner, the Democratic chair of the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence. That was at the 2022 Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas at a meal that included celebrity chef José Andrés. (When I pushed for more details on this “wild dinner,” Warner wouldn’t bite: “Note to self: Don’t say to a reporter, ‘It started with an evening in Vegas.’”)

“The kid was pretty impressive,” the senator said. He paused, then edited himself. “Not ‘kid.’ I should say: The guy was impressive.”

To some people who have known Wang the longest, he hasn’t changed all that much since he really was a kid in Los Alamos, N.M., one who liked to jot down startup ideas in a Google Doc during ninth grade and was eager to speak his mind.

“Even when we were kids, if Alex disagreed or had his own view of things, he was never shy of expressing it,” said Scott Wu, his friend since sixth grade, who now runs his own billion-dollar AI startup, Cognition Labs. As teenagers, Wu and Wang initially bonded over their shared love of math competitions.

“Competing was almost our love language,” Wu said.

Wang enjoyed a dizzying number of academic pursuits, including playing the violin and participating in debate tournaments. His parents, who worked as physicists at the Los Alamos National Lab, the birthplace of the atomic bomb, decorated their house with trophies from math, coding and physics competitions that he and his two older siblings won.

It was a demanding childhood, and it left Wang in a permanent “pursuit of excellence almost at all costs,” said his friend Victor Lazarte, a Benchmark venture capitalist. Lazarte described the mentality driving Wang as “How can you push yourself to go as far as you can?”

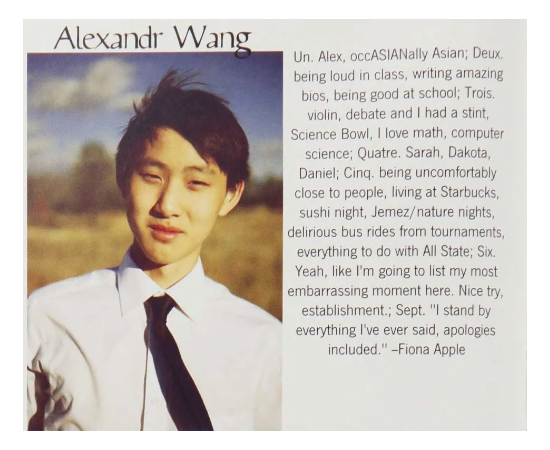

In high school, Wang raced ahead of his classmates in math and got into Phillips Exeter Academy, the elite New Hampshire boarding school. His parents, however, wanted him to stay in New Mexico, which frustrated Wang, a close high school friend recalled. “He felt he had unfulfilled potential in Los Alamos,” the friend said. Indeed, it seems Wang felt at one remove from his high school classmates. In his senior year book, he quoted singer Fiona Apple: “I stand by everything I’ve ever said, apologies included.” And in the page next to his senior headshot, where some classmates listed their most embarrassing moment, Wang refused, writing: “Nice try, establishment.”

When he applied to colleges, he received a heart-breaking rejection letter from Harvard University but won a spot at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Rather than head east immediately, though, 17-year-old Wang went to Silicon Valley, taking coding jobs at Addepar, an investing software startup, and Quora, a question-and-answer site.

Despite his fast start, Wang confessed in a public Quora post at the time that he felt an imposter syndrome: He didn’t really relate to either his older co-workers or the local college students he tried to hang out with. “I fit imperfectly between two worlds,” he wrote.

Wang tried to mitigate the situation by studying the patterns of Silicon Valley startup life as much as he could. He would talk about those rhythms often with Wu, his childhood friend, who had taken an Addepar internship and who roomed with Wang in Mountain View, Calif.

“We’d always talk about different leaders and how different decisions were made: This was right, this is wrong, how this could be done better,” said Wu.

At Quora, Wang struck up a friendship with another young person, Lucy Guo, who was a former Thiel Fellow and worked at Quora as a product designer. They decided to team up.

In 2016, once Wang had dropped out of MIT after a couple semesters, he and Guo tried their hand at building their own startup. They ditched one early half-baked idea, a concept some friends heard them call “ClassPass for clubbing.”

But they got into Y Combinator, which Altman then ran, and worked on another idea, a virtual assistant named Ava. Wang and Guo struck other YC participants as quiet and smart but generally unremarkable. “If you looked back from the first week, they didn’t look like a clear winner of the YC hunger games,” said a fellow YC founder who knew the pair then.

They made a third switch to a project they called Scale API, which would offer software developers “humans on demand” for outsourcing microtasks like image annotations and audio transcription.

Dan Levine, then a 28-year-old investor at Accel, was intrigued, particularly by Wang’s background as a 17-year-old manager of an engineering team at Quora, a startup known for its technical chops. “I thought that was extremely odd,” Levine recalled. Perhaps it was odd, but it was a marker in Wang’s favor nonetheless: Levine wrote a check for Scale before YC Demo Day, surprising other founders in the program.

Afterward, Wang and Guo went to work out of Levine’s Mission District apartment. From there, Wang, Scale’s CEO, helmed a small team of engineers and worked with customers, while Guo worked on operations and design.

One early smart decision: Scale wanted customers to think of it as a provider of critical software infrastructure rather than just another outsourcing firm. It would try to sell its service more to software developers, as Stripe and Twilio had done, rather than to less technical executives.

Much of Scale’s early business came from the boom in autonomous vehicle technology sweeping across Silicon Valley at the time. Companies like Alphabet’s Waymo and General Motors’ Cruise needed to train AI algorithms that would let cars operate on their own, and Scale was in a prime position to help. No other outsourcer had data-labeling capabilities for the type of three-dimensional images generated by the autonomous vehicles’ radars and sensors.

Scale engineers initially built the 3D-labeling product in a couple months for Nuro, an autonomous-delivery startup. Cruise, Waymo and even Apple became Scale customers, too.

By the end of 2017, Scale was employing over 1,000 labelers, largely in the Philippines, a country with a convenient combination of cheap labor and a prevalent videogame culture, which meant the company could find enough people with the high-end computers required to do the work. (On average, contractors earned about $1.50 an hour for 10 hours of work per week, Scale later told investors.)

Scale paid the contractors based on how well they did the work, however, rather than paying an hourly wage, which kept costs down. That also meant contractors often needed to excel to earn a substantial paycheck. The setup was far from perfect. Scale’s system for payouts didn’t always work well, several former employees said, leaving workers with paychecks that were delayed or never came at all.

In San Francisco, Wang’s startup operated from a small South of Market office, with few luxuries. The toilet sometimes broke. Software engineers often had to label tasks themselves to make up for a shortfall in contract workers.

Wang needed more staff as the startup grew. He was a voracious recruiter, often using poker games as a way to meet fellow math-loving and competition-hungry engineers. His unlikely pitch to fresh MIT grads—to throw themselves into solving an unsexy data labeling problem—often landed. But he didn’t always win in poker, sometimes aggressively overplaying his hands, said a friend who has played with him.

Soon Wang had a more serious problem than a malfunctioning toilet: a festering dispute with his co-founder, Guo, which spilled into the view of other employees. Wang grew frustrated with how Guo was running the operations team, a key part of Scale as it set up computer facilities in faraway countries.

Guo, meanwhile, thought Wang wasn’t doing enough to fix problems with contractor payments. She told others at the time she wanted Wang gone and wanted to change the startup’s culture.

But Wang had the upper hand in the fight, given his CEO role and the fact that Levine, the other board member, was on his side. Wang fired Guo in 2018. (“We had a difference of opinion but I am proud of what Scale AI has accomplished,” Guo said in a statement.)

With internal turmoil out of the way, Wang put a lot of his focus on customer relationships. Some early Scale customers like Oscar Beijbom, the machine-learning lead at nuTonomy, a self-driving car startup, remembered Wang as “a larger-than-life person: fast talker, fast thinker.” Scale became the go-to data-labeling provider to autonomous vehicle startups because it offered cheap prices, and because “there was no established really good player,” Beijbom said.

But Beijbom said he found too many mistakes in the company’s data-labeling work. In some images, for example, Scale had labeled a building’s windows as pedestrians. “They weren’t as good as [what] they were selling,” Beijbom said.

Over time, Wang developed a routine for how he liked to run Scale’s all-hands meetings: He wanted each session to end with employees asking him hard-hitting questions. In 2019, one employee asked about poop.

The employee offered a hypothetical to Wang: Would Scale work with a smart toilet company if it meant sending images of feces for contractors to label? It sparked a debate about what kinds of businesses Scale would get into next, two former employees said.

Wang had set some boundaries already. He had avoided pushing Scale into the dark world of content moderation, where some contractors have to look at child porn and death threats. But what about the defense industry? “We will not help build killer robots,” Wang said at the meeting, the two employees recalled.

The conversation about new industries to pursue was timely. Wang wasn’t having trouble raising more money from investors, and in mid-2019, he secured a billion-dollar valuation for Scale in new funding led by Peter Thiel’s Founders Fund, which had previously backed government contractor Palantir.

But Wang needed a fresh source of revenue: The boom in autonomous vehicles was starting to dissipate, and startups like automated shuttle service Drive.ai had sold in fire sales.

At the time, Wang was overoptimistic in his forecasts. In 2019, the company said it would hit $121 million in revenue in 2020, but it only hit about $70 million, according to investor presentations.

To fill the gap between expectations and reality, Wang headed to Capitol Hill to secure new revenue, which meant abandoning his vow to avoid working with defense clients. In 2020, Scale won a $90 million, five-year contract to help the Department of Defense “experiment, develop and iterate on high-quality annotated datasets for artificial intelligence,” the agency said. The next year, the San Francisco startup hired a small team in Washington.

Some employees didn’t celebrate the win, said Matthews, the former Scale employee. They sent in questions about the contract during an all-hands meeting. Wang dismissed their concerns. Of course Scale would continue work with the defense industry, he said. “He seemed unbothered by their opinions,” Matthews said.

Eventually, a far greater source of revenue quickly emerged back in Silicon Valley: the explosion in generative AI companies. By 2019, OpenAI had become a Scale customer, and Scale engineers worked with OpenAI to incorporate human feedback into how it trained its AI models.

When ChatGPT’s splashy debut in November 2022 set off a surge of investment in AI across tech, Wang changed Scale’s business substantially—dropping some of the cheap overseas worker outposts and starting to employ people with doctorates, lawyers and doctors who could help LLMs actually spit out humanlike responses.

Scale needed to remake many of its software tools as the startup shifted from labeling imagery for autonomous vehicles to training AI models. It also needed to improve its payment software for contractors, many of whom were now working out of wealthier countries.

In addition to working with OpenAI, Wang scored contracts with Meta and Alphabet, and Scale’s revenue spiked, going from an annual pace of $227 million in 2022 to $680 million the next year. The growth came at a cost: For the year, Scale’s gross margins had fallen to 49% from 59%—partly the result of those higher-paid contractors.

Eager to keep the party going, Wang set out at the beginning of this year to raise more funding at a $14 billion valuation, nearly double the previous number. Some prospective investors Wang approached had doubts about whether Scale deserved such a price tag: Its revenue seemed highly concentrated, with only a handful of big customers. And if AI turned out to be a short-lived mania, the contracts would fade quickly, as those from autonomous vehicle clients had done previously.

Wang pitched impressive numbers and bold forecasts: 206% revenue growth for 2024 and profits, at least on an adjusted basis. He compared Scale to Nvidia, saying his startup could match the older giant’s revenue growth and gross margins. And he boasted about having already won over major firms like Meta and OpenAI as customers.

Wang’s talk wasn’t enough to sway some wary investors. It took him several months to close the round. The investor that ended up leading the round was one of Wang’s earliest believers and backers: Accel.

With the new cash, Scale still has a substantial amount of growing up to do, and some current investors don’t think it’s particularly close to going public.

It needs to build out a larger, more experienced sales force to sell AI apps to banks and insurance companies, prospective investors said. To reach an IPO, it will likely need to strengthen its corporate governance by adding more directors who have no ties to Wang.

Right now, Scale’s board consists of just four people: Wang; his close friend, Plaid co-founder Will Hockey; and two longtime Scale investors, Accel’s Levine and Index Ventures’ Mike Volpi. Plus, an inconsistent workflow and buggy systems have turned off contractors who’ve worked for Scale on projects for OpenAI and Google.

While AI mania has meant an influx in sales, it has also led Wang to fret recently about falling behind in the scrum for hiring top employees. The company’s Glassdoor reviews are more negative than those of many of its startup peers, for instance. It has a 3.5 rating, significantly lower than startups such as OpenAI (4.3) and Figma (4.4).

To differentiate Scale from competitors like OpenAI and Anthropic, Wang recently went full provocateur.

Earlier this month, he made a public promise on X to hire future staffers like software engineers and operations leaders based on “merit, excellence and intelligence,” an implicit critique of the hiring initiatives based on diversity, equity and inclusion many in liberal Silicon Valley favor. (OpenAI and Anthropic are widely seen as having left-leaning workforces.) This pledge—part of Wang’s unending campaign to expand his profile—won him praise from the billionaire right, including props from Elon Musk, Palmer Luckey and Wall Streeter Bill Ackman.

He meditated on his relationship with the public and the press in a recent interview with investor Harry Stebbings on the latter’s founder-friendly podcast, “20VC.” “I received more fair treatment testifying in front of Congress than I have from various media outlets over the years,” Wang lamented.

In the conversation, he and Stebbings discussed how founders become inextricably tied to their startups. “If you look at the amount of times Sam Altman trends versus the amount of times OpenAI trends, it is disproportionately higher for Sam Altman,” Stebbings said. “People now more than ever love the cult of personality.”

Wang agreed with the assessment. “Fascinating,” he said. “It probably speaks to a deep human need.”

Kate Clark contributed to this story.

Cory Weinberg is deputy bureau chief responsible for finance coverage at The Information. He covers the business of AI, defense and space, and is based in Los Angeles. He has an MBA from Columbia Business School. He can be found on X @coryweinberg. You can reach him on Signal at +1 (561) 818 3915.