The Looming Debt Crunch Facing Tech Companies Like The RealReal

Redfin, with a market capitalization of less than $600 million, had $1.3 billion of convertible debt on its books as of September. Photo by Bloomberg.

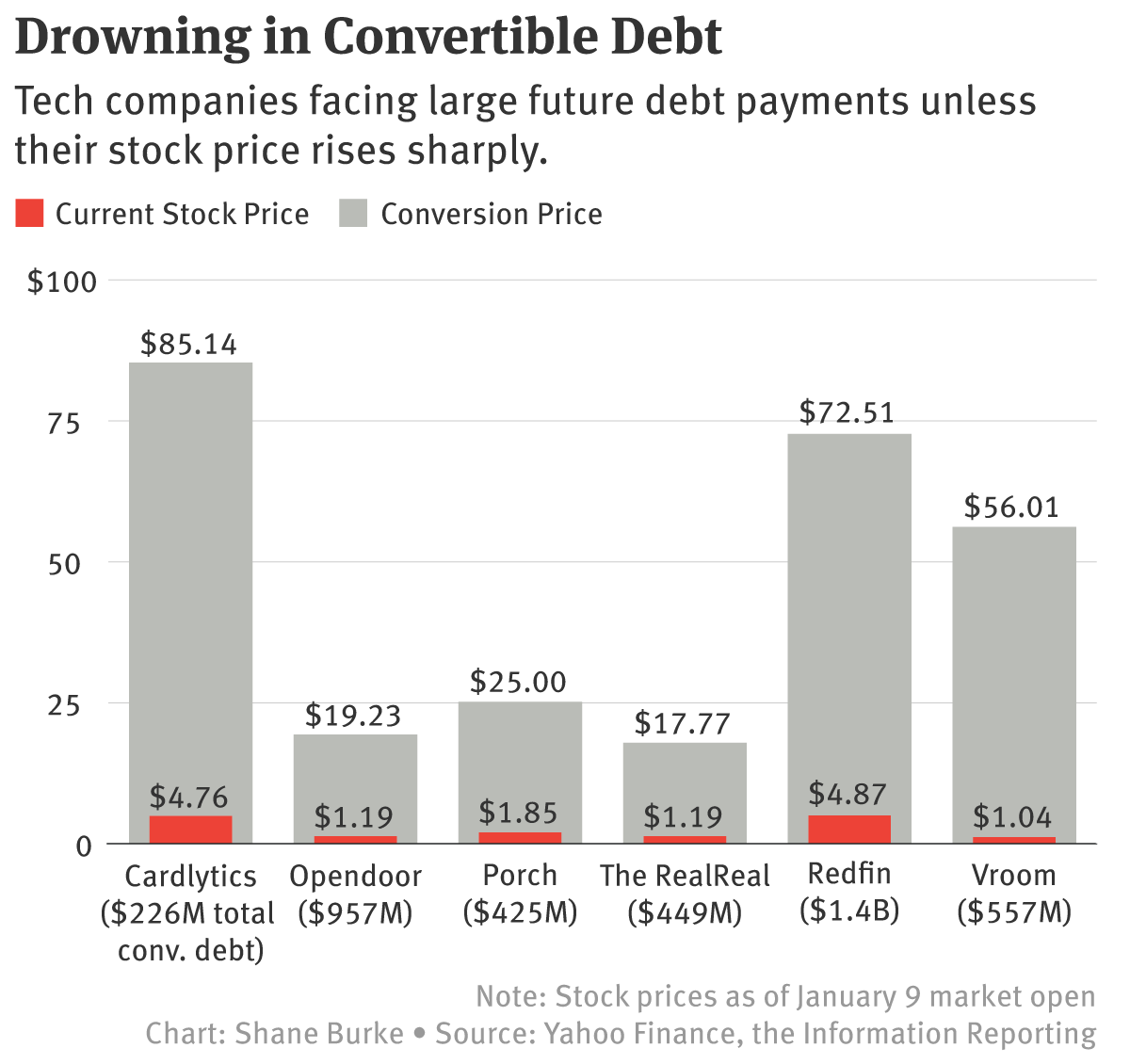

Redfin, with a market capitalization of less than $600 million, had $1.3 billion of convertible debt on its books as of September. Photo by Bloomberg.In 2020, a wave of public tech companies—including The RealReal, Vroom and Redfin—began selling record amounts of ultra-low-interest bonds that would convert into shares if the companies’ stocks kept soaring. Instead, stocks have been crushed, and a wall of potentially crippling or course-altering debt now looms over some firms.

Several companies that sold convertible debt likely will struggle to refinance it or find the cash to pay it off unless their fortunes turn around soon, according to interviews with investment bankers and an analysis of companies’ financial statements. If they do refinance, it will likely be much pricier. For some companies, the crunch could lead to efforts to sell themselves.

The Takeaway

Powered by Deep Research

While the bonds don’t mature for two or three years in many cases, several capital markets bankers said companies need to start figuring out in the coming months how they will pay off their debts if their stock prices don’t recover. To start cleaning up the debt, executives at Vroom and Redfin have recently said they would repurchase some of the convertible bonds from investors, as their prices have sunk.

To figure out how to pay off the debt, chief financial officers “are starting to explore the art of the possible,” said Viral Patel, global head of technology investing for Blackstone’s credit division. “You have to take care of it at least a year in advance.”

According to an analysis of filings by The Information, at least seven tech companies are burning cash while carrying convertible debt loads that come due in 2025 or 2026 and exceed the entire market value of the firms themselves. They include online marketplace The RealReal, real estate firm Redfin, home seller Opendoor, used car seller Vroom and marketing tech platform Cardlytics. (Only Opendoor has enough cash on hand if it wanted to pay its debt today.)

The problem is particularly acute for these types of companies, with thin balance sheets, little or no cash output and depressed stock prices. For example, the amount of convertible debt The RealReal owes, about $450 million, exceeds the cash on its balance sheet and the company’s $115 million market capitalization. As of Monday’s close, the company’s stock price was $1.17. It would need to rise more than 1,400% in the next two and a half years for the first slug of debt to convert to equity. (One thing in The RealReal’s favor: 60% of its convertible debt doesn’t mature for five years.)

With interest rates low and stock prices climbing, tech companies from Airbnb to Zillow raised scads of convertible debt in recent years with ultra-low interest rates from 0% to 3%. A combined $104 billion was raised in back-to-back record years in 2020 and 2021, according to Dealogic. Convertible bond buyers, including a variety of hedge funds as well as asset managers like Allianz and BlackRock, lapped the offerings up.

The way the bonds work is fairly simple: If stock prices climb above a target level, often around 30% over a span of three to seven years, the bonds convert to stock and the company is off the hook for repaying investors in cash. But if the stock doesn’t hit the target by the time the loans come due, companies have to refinance them, buy the bonds back or repay investors in cash.

“At the top of every cycle, companies start to believe their share prices will forever go up and to the right, and that’s when they get in trouble with convertibles,” said Carl Chiou, head of technology equity capital markets at William Blair, an investment bank.

He added that companies were able to raise significant amounts of convertible debt because their stock prices had risen so significantly. “If you issue too much convertible debt when your stock is high, assuming it will convert to equity, you may have refinancing risk when the market corrects, as we’re seeing now.”

Some companies even doubled down on the bet that their stock prices would skyrocket by buying financial derivatives that would further increase the price at which the debt would convert to equity. They used this to hedge against potential dilution that would hit shareholders if the debt converted to equity.

The bets have backfired, as they won’t pay out unless the companies’ stock prices rise significantly. The RealReal spent about $56 million on these derivatives, called capped calls, in tandem with the convertible debt it raised. That cash represents about 19% of the total amount that currently sits on its balance sheet. 2U, an education tech company, spent $50.5 million, or 27% of its current cash balance.

Companies whose convertible bonds are underwater have a range of options, depending on their financial pictures. DocuSign, Palo Alto Networks, Okta, Block and Splunk, for example, have depressed stock prices and significant convertible debt coming due within the next two years—but they each also have at least $1 billion in cash on hand and generated cash in the past year. That gives them more options to pay off debt with cash or refinance with new loans.

As a general rule, companies typically will only refinance convertible debt at a maximum of 30% of their market capitalization. Companies with huge convertible debt loads relative to their size will have a tougher time refinancing, bankers say.

Instead, their options include renegotiating with bondholders to lower their outstanding debt or extend the due date in exchange for paying more interest, said Diana Doyle, who leads Morgan Stanley’s convertible debt business aimed at tech companies. They could also sell shares in the public equity market to pay off the debt, although that would be “painful” with their stock at low prices, she said.

“It’s good corporate hygiene for companies with convertible debt maturing in 2025 and 2026 to start thinking now about the range of options,” said Doyle, who also co-leads Morgan Stanley’s tech equity capital markets unit.

Companies’ debt loads could hasten potential deal-making, bankers and lenders said. For instance, when Zendesk sold itself in November to a group of investors led by private equity firm Hellman & Friedman, it carried about $1.2 billion in convertible debt, due in 2023 and 2025, most of which was unlikely to convert to equity. The debt outstanding was roughly equal to the amount of cash the company had.

The debt coming due also raises the stakes for firms to get profitable. On an August earnings call, an analyst asked Redfin executives how they planned to address their $1.3 billion of outstanding convertible debt. The real estate company burned about $100 million in cash last year and has a half-billion dollars of cash on hand.

Chris Nielsen, Redfin’s CFO, replied that the company planned to start generating profits by 2024. “That sets the stage, then, for us to feel really good about the capital position that we’ll have as those notes start to become mature,” he said.

Cory Weinberg is deputy bureau chief responsible for finance coverage at The Information. He covers the business of AI, defense and space, and is based in Los Angeles. He has an MBA from Columbia Business School. He can be found on X @coryweinberg. You can reach him on Signal at +1 (561) 818 3915.