Section 230 May Finally Get Changed as Lawmakers Prep New Bill

A bipartisan threat to repeal the legislation is part of a broader push from the Trump White House to force tech companies to accept different rules.

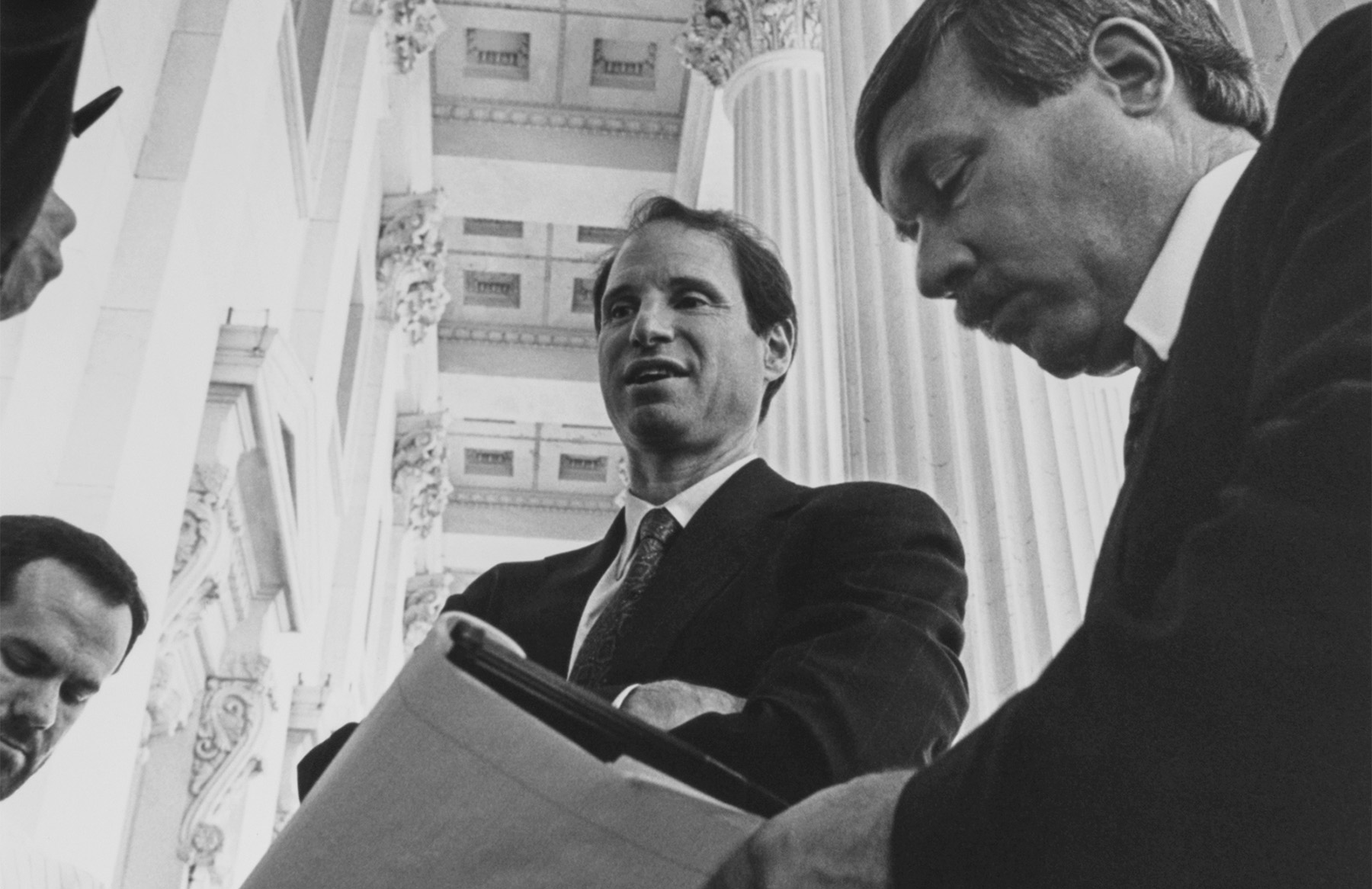

In June 1995, two young congressmen reached across the aisle to introduce legislation that would become the defining legal protection of the internet era: Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, which shields internet companies from liability for content created by users.

Now, nearly 30 years later, another bipartisan duo hopes to drastically alter that law. With both parties aligned—and President Donald Trump seemingly interested too—they stand a better shot at actually accomplishing the task than those who’ve previously attempted it.

As early as next week, Sen. Dick Durbin, a Democrat, and Sen. Lindsey Graham, a Republican, plan to introduce a bill that would set an expiration date of Jan. 1, 2027, for Section 230, according to a congressional aide familiar with the bill’s development. The senators have wide-ranging support from their respective parties: Republicans Josh Hawley and Marsha Blackburn and Democrats Sheldon Whitehouse and Amy Klobuchar have agreed to co-sponsor the bill. And two more Democrats, Richard Blumenthal and Peter Welch, have discussed joining as co-sponsors.

If all goes according to plan, Durbin and Graham’s proposal would be the first bipartisan bill introduced in Congress that could repeal what’s often lauded as the 26 words that created the internet.

The lawmakers say they don’t want to fully dismantle Section 230, which would have profound implications for free speech online and would devastate swaths of the tech industry. Instead, they hope the threat of an impending repeal date will push tech companies to engage in good-faith negotiations over new regulation—something the industry wouldn’t be keen to do without an ultimatum.

“The idea would be to force them to the table, and if they don’t come to the table and agree to meaningful reform, then ultimately Section 230 would be repealed,” said the congressional aide.

Nonetheless, the plan has left longtime defenders of Section 230 aghast. Eric Goldman, a professor at Santa Clara University School of Law and a co-director of its High Tech Law Institute, likened the effort to “a form of extortion.” Adam Kovacevich, founder of center-left tech lobbying firm Chamber of Progress, described it as “hostage taking.”

Even if Durbin and Graham fail, there are plenty of others waiting to take a swing at Section 230. Tech animus among lawmakers has reached a fever pitch, propelled by mounting safety concerns for kids online and congressional frustrations over years of failed efforts by legislators to deliver on promises to regulate big tech.

President Trump himself has long advocated for Section 230’s repeal, and Brendan Carr, whom Trump recently tapped to chair the Federal Communications Commission, has repeatedly stated that he believes the agency has the authority to reinterpret Section 230—despite decades of precedent and a recent decision by the U.S. Supreme Court suggesting otherwise.

Carr will likely face few obstacles in implementing his agenda, if he so desires. One of the FCC’s two remaining Democratic commissioners recently announced plans for an early resignation, and Trump’s shock firing of Democratic members of the Federal Trade Commission this week shows the administration has little tolerance for opposition—or political norms.

At the same time, judges around the country have been slowly but surely chipping away at Section 230, issuing a slew of conflicting and often difficult-to-interpret rulings that make it harder for tech companies both big and small to predict their liability risks. And a deluge of pending cases regarding social media addiction will only further muddle the legal landscape, using novel legal theories that aim to sidestep Section 230 protections in an effort to hold tech giants accountable for alleged harm to children.

Kovacevich, who has worked in the tech and public policy space for two decades, said tech companies are currently facing an unprecedented volume of attacks, particularly taking into account the dozens of state bills introduced in recent months. When it comes to Section 230, he worries lawmakers don’t realize the potential consequences of their actions.

“I think most members of Congress tend to think of repealing 230 as a punishment for tech,” said Kovacevich. “But the reality is that without 230, platforms would either look like Disneyland, which would be a sanitized environment where every user post had to be pre-screened, or it’d be a wasteland, where essentially they never looked for anything and every platform looked like 4chan, because they didn’t want to have liability for even looking at potentially defamatory content.”

“I don’t think either one of those outcomes is very good,” he said.

Section 230 may have emerged as a high-profile target for U.S. politicians in recent years, but the irony is that it had pretty humble origins. It was initially signed into law as an inconspicuous addendum to the controversial Communications Decency Act of 1996, which sought to tamp down on online pornography.

At the time, the U.S. was deep in the throes of a moral panic over kids’ online safety. (Sound somewhat familiar?) The mood of the nation is perhaps best epitomized by Time Magazine’s now infamous July 1995 cover, which featured a ghastly image of a young boy staring mouth agape at a computer screen above the text: “CYBERPORN…A new study shows how pervasive and wild it really is. Can we protect our kids—and free speech?”

The accompanying story referenced a study from researchers at Carnegie Mellon University. It found that 83.5% of images on online message boards were purportedly pornographic, and that these images were even more obscene and deviant than the porn typically available to purchase on video and in print—or at least that’s what it claimed. Shortly after publication, the study was largely debunked—rather than scanning the broader internet, the researchers had surveyed mostly paywalled adult-only message boards—and Time was castigated for misrepresenting the findings as factual.

Still, the story took off, igniting anxieties nationwide and fueling calls for congressional action. Republican Sen. Charles Grassley even entered the full text of the article into the Congressional Record as lawmakers debated the Communications Decency Act, which made it a federal crime for website operators to make porn available online where kids could come across it.

Lawmakers added Section 230 to the bill to incentivize content moderation, hoping the protection from litigation would make tech companies feel secure enough to do so. The provision shielded websites and other online platforms from liability for “good faith” efforts to remove offensive content, even if they made mistakes in the process. It also barred treating platforms as the publishers of any content generated by their users.

Congress passed the act in February 1996, and President Bill Clinton quickly signed it into law. The following year, the Supreme Court struck down much of the legislation, ruling unanimously that its anti-indecency provisions violated the First Amendment. Yet the justices allowed Section 230 to remain, and that shield helped usher in the digital age.

Bolstered by the expansive new protections, internet companies took up novel screening practices—from email spam filters to message board moderation—that aimed to make the web a more hospitable and easy-to-navigate place. But they soon encountered pushback from critics claiming that their content moderation efforts weren’t aggressive enough, particularly when it came to protecting children from accessing online pornography.

These concerns led to laws—and legal challenges to overturn those laws—but by and large, internet companies remained reluctant to take up wide-ranging content moderation, seeing it as an unnecessary expense. After all, they had legal immunity: Why spend the money?

For more than a decade, the tech industry was largely allowed to hold on to that mindset unchallenged. That started to change in the mid-2010s, and as tech has grown into a cornerstone of the U.S. economy, the once little-known piece of legislation has become a form of shorthand for the industry’s ills.

Democrats (and some Republicans) tend to blame Section 230 for what they view as tech companies’ failure to more aggressively police problematic online content, like drug sales on Snapchat, sextortion scams on Instagram and child sexual abuse material on dating apps. Conservatives, on the other hand, castigate Section 230 as a way for tech companies to overmoderate speech or allegedly censor differing political view points online.

Yes—one group says the legislation allows tech companies to get away with too little, while the other group says it allows them to get away with too much. The two visions are fundamentally in conflict, yet both have prompted calls for Section 230’s reform. That urge has intensified with Congress’ repeated failures to pass any new regulation of the tech industry, including, notably, the 2024 death of a package of bipartisan kids’ online safety legislation in the House of Representatives.

The effort to repeal Section 230 spearheaded by Durbin and Graham would introduce a bill that would look “very similar” to legislation proposed by Graham and Republican colleagues in 2021, a congressional aide familiar with it said.

Graham met with Durbin originally to discuss co-leading a bipartisan version of the bill last year, but the two ultimately decided to hold it until the current Congress was in session, fearing it might get lost in the tumult of the 2024 election cycle, that person said.

Durbin and Graham had initially planned to introduce the legislation in February to coincide with a Senate Judiciary Committee hearing on child safety, but unexpected turmoil in U.S.-Ukraine relations ultimately ended up taking priority for Graham’s office, temporarily delaying it again, the aide said. They are likely to introduce the bill when Congress returns from recess next week.

Lawmakers hope to use the threat of Section 230’s repeal as a cudgel against the tech giants they view as impeding reform efforts. But it’s unclear exactly what that reform would look like, as legislators’ previous attempts to rework 230 have varied wildly in terms of scope, focus and intended effect.

Historically, GOP reform efforts have targeted the part of Section 230 that says a website can’t be sued for taking down content. If Congress or Trump’s newly emboldened FCC chair weakened or eliminated the protection, that would disincentivize online platforms from moderating user content and using automated filters to improve the user experience. This aspect of the law is “actually critical,” said Goldman, the law school professor. “This is the foundation of efforts to block spam, spyware, viruses, and also the foundation for parental control filtering software.”

Meanwhile, reform efforts led by Democrats (which have occasionally included Republicans) have typically targeted another part of Section 230 that says a platform can’t be sued for what it leaves up on its site. “Democrats think that if the internet companies just had more legal incentive, they would be more aggressive about removing antisocial content,” said Goldman. He thinks it would have a different effect: a much more sparse internet, where “the good stuff is going down with the bad” as companies take a wide-sweeping view on moderation.

Goldman pointed to the legacy of FOSTA-SESTA—the first exception to Section 230 immunity ever enacted—as an example of the unforeseen consequences of this approach to reform. Congress enacted the package of legislation in 2018 in an effort to curb human trafficking and make it easier for victims to hold platforms accountable for the role they play in facilitating illegal activity. The bill aimed to do so by limiting Section 230 protections so platforms could be held legally liable for any user content that helped enable sex trafficking.

“It didn’t work,” said Kendra Albert, a technology lawyer and academic who has chronicled the legislation’s consequences. The law didn’t prompt a wave of litigation challenging the tech industry’s practices, as its proponents had hoped. Instead, in response, social media sites and other platforms elected to ban broad swaths of content relating to sex and sex work, Albert said. That had dire consequences for members of the sex worker community, many of whom found themselves barred from online organizing and resource-sharing spaces.

Albert finds it “incredibly concerning” that Congress once again has its sights set on Section 230. “I feel like we’ve learned none of the lessons,” Albert said.

While further changes to the law could hamper wide parts of the tech economy, one group stands to benefit from Section 230 reform: traditional media, such as the companies behind the nation’s largest newspapers and magazines. Those publishers have long felt Section 230 created an uneven playing field, said Chris Pedigo, who leads government affairs for Digital Content Next, a trade organization representing businesses including The New York Times, NBCUniversal, and Condé Nast.

“Publishers are held liable for the content that they create and are often subject to libel suits. Meanwhile, platforms who are their main competition for advertising are not held to the same standard,” said Pedigo. If platforms lost Section 230 protections and suddenly had less content, that could be a boon for publishers.

“That would significantly curtail the amount of ad space they would be able to sell,” said Pedigo, which could send advertisers running back to traditional media in a reversal of a decadeslong trend toward digital media. “I think it might call into question whether the service”—that is, advertising in social media feeds—“was really worthwhile to begin with.”

Peter Chandler, executive director of the Internet Works Association, which represents small and medium-size tech companies like eBay and Reddit, described the potential consequences of a Section 230 repeal more bluntly: “It would be absolutely devastating.”

Paris Martineau (@parismartineau) is a feature writer and investigative reporter for The Information's Weekend section. Have a tip? Using a non-work device, contact her via Signal at +1 (267) 797-8655.