Graphic by Clark Miller

Graphic by Clark MillerTales from the Shredder: How a Quarter-Million Fired Tech Workers Are Picking Up the Pieces

Ripped away from once-safe jobs, tech workers face a reckoning—should they come back? What they decide will shape the next decade in tech.

On a brisk Wednesday in December, Pakin Wirojwatanakul made his usual commute to the downtown San Francisco office of fintech startup Plaid. But when he arrived, the front desk security guard told him to go home. Puzzled, he left the office and reversed his commute. Then he received a cryptic text from a friend: “Are you safe?” Back at home, a thoroughly confused Wirojwatanakul opened his email and finally grasped what was going on: He was being laid off, along with 260 other Plaid employees, or about 20% of the company.

By January 2023, nearly 250,000 tech workers had lost their jobs in a similar fashion over the past year. Many received the news via brusque, formal emails sent to their personal addresses. Others were beckoned via calendar invites to 15-minute meetings with the human resources department. A strategist at Slack, who was on vacation during the company’s layoffs, found out she had lost her job when a colleague texted condolences and said it had been nice working together. A Google engineer discovered he’d been laid off only when he searched his spam folder; ironically, Gmail had flagged the email from Google HR as suspicious.

Over the last year, I have frequently wondered what would become of those quarter-million fired tech workers. Their stories seemed to evaporate after their last day of work, sealed with a perfunctory post on LinkedIn. Where, I wondered, would they all end up? Would they get reabsorbed into other tech companies that, improbably, have continued to hire? Would they abandon the industry, feeling burned after their corporate breakups? Or would they make creative use of their severance payments—four months of base pay on average, or in rare cases as much as a full year’s salary—and set out to build something new of their own?

In recent weeks, I spoke with more than 30 tech workers who lost their jobs in the havoc of the past year. They ranged from entry-level employees navigating their first downturn to Silicon Valley veterans who had survived more than one boom-and-bust cycle. For the most part, these workers fell into one of two camps: those who viewed the job loss as a personal trauma and those who saw the layoffs as liberation. Taken collectively, their next steps offer a glimpse at a reconfiguration of the tech industry—call it the Great Re-Sorting. Talent is trickling out of large tech companies and into early-stage ventures or other industries altogether, and the modest diversity gains seen over the last decade are in danger of reversal.

Most of these workers spoke to me on the condition of anonymity because their separation packages required them to sign nondisparagement agreements. Others were actively job seeking and feared jeopardizing their chances of getting hired. Almost all told me that because of their ex-employers’ generous severance packages, the cost of layoffs had been more existential than economic. A former project manager at Lyft compared the experience to a confidence-shattering breakup: “You go through the emotional turmoil of like, ‘Am I worthy? What did I do wrong?’”

One former Plaid engineer, laid off the same day as Wirojwatanakul, said that while he had already found a new job at a large tech company, he was still recovering from the bruising experience of getting sacked. “They paid us well; they gave us good severance,” he said. “But the experience made me feel like I was just a tool. If they need you, they hire you. If they don’t need you, they discard you.”

The Good News: ‘Surplus Elites’ Are Still Being Hired

People have all kinds of names for what has happened in tech over the past year. Scott Galloway, marketing professor and podcaster, has dubbed it the Patagonia Vest Recession. The venture capitalist hosts of the “All In” podcast have referred to it, more mercurially, as a culling of “surplus elites.”

But even with widespread layoffs brought on by the severe market correction (the NASDAQ is down 33% from a year ago), unemployment rates within the tech sector have remained staggeringly low. In January, a mere 1.5% of tech workers were unemployed per the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. “We saw 150,000 layoffs in 2022. That’s like, one half of one month’s open job postings from last year,” said Art Zeile, CEO of DHI Group, which owns the tech career marketplace Dice.

Dice’s research found that in 2022, job postings for tech jobs actually increased 25% compared to 2021, despite hiring freezes at large companies like Google and Apple in the second half of the year. Those new jobs have continued to open up at both traditional tech companies—like TikTok, which has thousands of openings on its career portal—and in industries like banking, consulting and defense, which have ramped up hiring for technical roles. The bottom line, Zeile said, was that tech workers who got laid off weren’t likely to be out of work for long. “People can, in fact, get a new job very quickly,” he said.

“It’s a weird mismatch,” said a former user experience researcher at Lyft, who was let go in November. “You’re seeing layoffs, layoffs, layoffs. And yet I’m still getting hounded by recruiters all the time.” He scored a few job interviews after recruiters saw his name on a spreadsheet of recently fired Lyft alumni. Some turned out to be dead ends—one recruiter, from DoorDash, ghosted him after the company did its own round of layoffs in December—but by January, he’d taken a job at another large tech company. “I know this is supposed to be a tough economic situation,” he said, “but you wouldn’t guess it based on how much people are emailing me.”

In fact, nearly three-quarters of tech workers who were laid off between January and October 2022 landed a new full-time job within three months, according to data from Revelio Labs, a workforce data company. About half of these workers even received a salary bump in their new positions.

For some tech workers, the combination of large severance packages and sustained interest from recruiters gave them the freedom to take a break between jobs. One former Lyft employee told me he finally joined a gym and started reading more books with the free time he’d carved out before taking a new job. “This has been the best vacation I’ve ever had,” he said.

Other workers said they felt pressure to find a new gig right away, either because they needed one for visa purposes or because their families relied on their income. Wirojwatanakul, the former Plaid engineer, has an H-1B visa, common among international workers in tech. He thought Plaid’s severance was extremely generous—four months of base pay, plus cash to cover six months of healthcare premiums—but his visa gave him no more than 60 days to find a new job after Plaid took him off the payroll. “If I had a green card or if I were a U.S. citizen, it could be like a nice vacation,” he said, “but for those of us on visas, it’s like our lifeline is gone.” (He has since signed a job offer and is waiting for the visa transfer to go through.)

A former Snap employee told me he started looking for new jobs the day after he got laid off, in September. “I was looking at my kids and thinking, ‘I don’t have time to relax,’” he said. Snap had given him four months of full pay, which he deemed more than fair, but he felt uncomfortable without having another job lined up. “Back when I was 25, I’d be like, ‘OK, cool. I’ll claim unemployment and play videogames.’ But that’s not an option now.”

Within ten days of losing his job, the former Snap employee signed a new offer to work for an artificial intelligence company. Looking back, he isn’t sure he needed to rush so much. “I’m still getting contacted from various companies trying to see if I still need a job,” he said. Despite mass layoffs, it seems, there is still plenty of work to go around.

The Bad News: Severance or Not, a Layoff Still Stings

While many of the fired tech workers I spoke to had already leapfrogged from one high-paying job to another, others seemed shell shocked and battered. One longtime Google employee who was let go in January lamented the end of feeling “psychological safety” in tech. It wasn’t his first time being laid off—he had been fired before, during the dot-com crash—but it was the first time in his 17-year career at Google that anyone had treated him as a disposable cog. In the past, Google gave eliminated workers enough notice to hand over their projects to someone else and always offered to help find them new jobs within the company. This time, there was no such aid. The experience left him feeling cynical about the company and the tech industry at large.

Other employees displayed similar bruises. A former communications lead at Twitter said that in the pre–Elon Musk days, the company had cultivated a culture with little separation between private and professional lives. People were encouraged to bring their whole selves to work and teams bonded on a personal level. “I felt like the people I worked with were my family—to a fault,” she said. “It’s what made this experience so rough.”

She had worked at Twitter for more than six years when, in November, rumors started to circulate that half the workforce would be axed. The employee was in the process of transferring a folder of wedding videos from her work laptop to her personal one when the screen suddenly went black. It was evening, and she hadn’t yet received any indication that her job was eliminated; she received the email the following day. “Having been at Twitter for that long, it just felt like such a sad way to end things,” she told me. “I understand being cut off from emails or Slack, but to not have access to the laptop you’ve been using for over six years, in the blink of an eye—it feels unnecessary.” Like the Google employee, she felt wary of returning to a tech industry that seemed so unlike the one she had joined years before.

Others I spoke to were trying to return to tech jobs, but found that things had fundamentally changed since they had last been hired. A recruiter who joined Shopify in the summer of 2021 told me tech seemed to be in hypergrowth mode when he joined. “It was like, ‘Don’t worry about headcount, just keep hiring,’” he said. A year later, in July 2022, Shopify laid off 10% of its workers—including the recruiter. He rebounded to another recruiting job at an enterprise software company, but got laid off again this January.

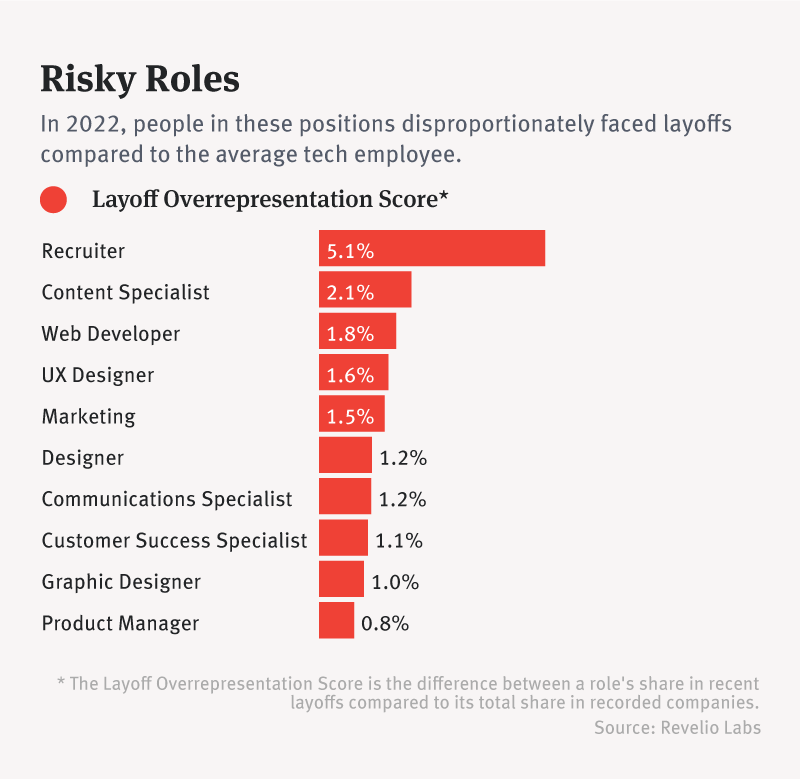

It stung to get laid off twice in six months, he said, but there was some small comfort in knowing he wasn’t alone. Data from Revelio Labs found recruiters were twice as likely as web developers to be laid off in the last year, and companies have been slow to hire them back. The former Shopify recruiter said he was looking for new opportunities on LinkedIn, but the few jobs posted had hundreds of applications by the time he reached them. “These are probably the people who were just let go at Amazon, whose résumés probably look better than mine,” he said. “It’s daunting.”

On the Other Hand: Layoffs Unlock Tech’s ‘Golden Handcuffs’

For tech workers dispirited by the new status quo, there is of course another option: ditching the industry entirely.

For John Espinosa, working at a company like Alphabet had been the fulfillment of a professional dream. But when he got laid off in January from his job as a technical program manager at YouTube, he began to reconsider what he waned out of life. Alphabet offered employees a 60-day notice period—essentially a garden leave, in which they remain on the payroll but are barred from the workplace—and an additional 16 weeks of base pay as severance.

Espinosa plans to use those six months as a recalibration period, taking improv classes and workshopping a stand-up comedy routine. He also has a side hustle going with a friend, designing fanny packs for festivalgoers. “I want to try to define a life that’s less focused around making as much money as humanly possible and more oriented around doing things that feed me,” he told me. “I hope that other tech folks can learn to think about the freedom that they could have.”

A few tech workers similarly described their layoffs in terms of liberation. Working in big tech had been impossibly seductive—the employees loved the free meals, nap rooms, on-call massage therapists and bundles of company stock that seemed to grow more valuable every day. But now, with the slumping of tech stocks and the erosion of perks, it seemed a lot less enticing to go back. In Meta’s last earnings report, Mark Zuckerberg called for a “year of efficiency.” If these companies wanted to act more like startups, that was fine, but that made it just as enticing to join—or even build—an actual startup instead.

For Taylor Lowe, a former product manager at Meta, the layoffs provided an excuse to do exactly that. Lowe had wanted to start a company for a while, but it never seemed like quite the right time. Then he got laid off in November, and suddenly there was no reason not to do it. “In my case, the timing worked out well,” he told me. “I was like, you know, this is the sort of compelling case for me to make the jump.”

Two of Lowe’s co-workers followed suit, resigning from Meta and joining him as co-founders. Their company, Metal—a developer platform for data analysis—is now going through Y Combinator, along with those of at least a few other big-tech defectors turned founders. James O’Dwyer, one of Lowe’s co-founders, said there was no longer an opportunity cost associated with leaving a job in big tech. “When you join these kinds of companies, you expect a certain level of security,” he said. “With that wiped away, it’s like, the math just doesn’t check out.”

People are also leaving big tech to work for smaller enterprises. Ryan Choi, who runs Work at a Startup, a hiring platform for YC-backed companies, told me he’d seen a massive influx of talent looking to get hired by such startups. Between June 2022 and January 2023, the number of job seekers on the platform tripled and there was a 500% increase in the candidates who had Amazon and Meta on their résumés.

The Collateral Damage: Inevitably, Some Workers Get Left Behind

In January, more than 300 tech companies announced layoffs, adding to an ever-rising tally of tech workers cut loose. Some companies, like Meta, are rumored to be planning more cuts soon. It won’t be entirely clear how the composition of the tech industry will change until the last domino falls. “We’re in this liminal time where everybody is sort of looking around, trying to figure out what the hell is going on,” said Aline Lerner, founder and CEO of interviewing.io, a mock interview platform for technical workers.

Paula Bratcher Ratliff, president of Women Impact Tech, described the last year of layoffs as an overall “reshuffling” of the tech industry, whereby workers simply moved between companies in an accelerated fashion. But when the dust settles, she said, we may find a tech industry that has been reshaped in important, unintended ways.

Ratliff’s group recently surveyed 1,500 tech workers who were laid off between September and November 2022 and found that twice as many women as men were still looking for jobs. “We tried to neutralize the data as much as possible, to compare people with the same titles, in the same geographical location, with the same educational backgrounds,” said Ratliff. “There was nothing other than gender that was a differentiator in landing new jobs.”

Ratliff believes a decade of work to bring more women into the tech industry may have been undone in a year. Women make up about one-third of the tech industry, but they represent 45% of tech layoffs since September, according to an analysis of data from Layoffs.fyi. Ratliff also worries about the impact on diversity programs in a year when tech companies have cut back their spending drastically. “If you peel back the onion, it’s the [diversity, equity and inclusion] executives and types of jobs who were heavily laid off,” she said. Companies may have a harder time attracting underrepresented employees if they lose their diversity gains to layoffs.

Those implications are just beginning. The gaps left behind by this season of layoffs may prove frustrating or embarrassing for the industry in the years to come. But for brand-new startups or industries outside tech, it offers an opportunity: a fresh batch of talent, waiting to be hired.

Arielle Pardes covers tech culture for The Information’s Weekend section. Previously, she was a senior writer at WIRED in San Francisco.