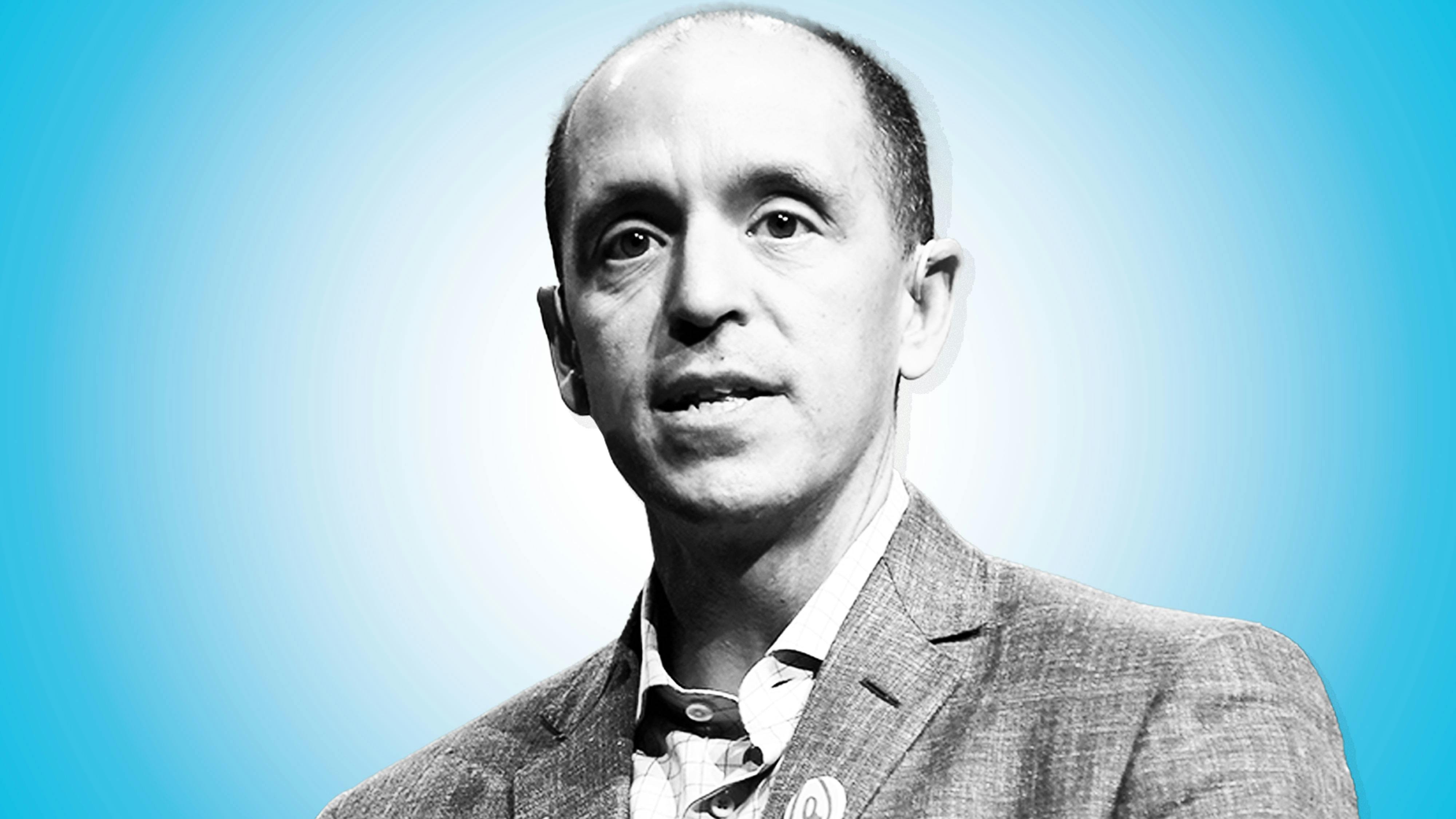

Airbnb’s Spin Master

Despite a combative reputation, former political operative Chris Lehane has emerged as the travel rental firm’s most influential executive next to CEO Brian Chesky. Now the public affairs chief is facing his toughest test yet: helping the company survive a devastating pandemic and pull off a successful IPO.

Chris Lehane was piping mad. Laurence Tosi, Airbnb’s chief financial officer, had accused the Airbnb policy and communications chief of spending millions of dollars before Tosi had signed off on the plans, approval Lehane didn’t think he needed.

Their dispute flared up near the parking lot behind Airbnb’s headquarters one morning in 2017. Co-workers witnessed Lehane yelling and cursing at Tosi before storming past the CFO. The episode, described by multiple people familiar with it, became lore inside parts of Airbnb. Some staffers who witnessed it walked back to the office shaken, one of the people said. “Oh, the famous parking lot thing,” a current high-level employee described it.

It wasn’t the first time Lehane had clashed with a colleague. He frequently battled others in the upper ranks of Airbnb over financial and strategic questions, though the arguments weren’t usually so heated. More often than not, current and former co-workers said, he won those fights, through both deft handling of internal politics and a keen outsider’s sense of how the startup was perceived far from its San Francisco home base. His ability to anticipate and manage public relations crises, aided by his years of experience as a political operative, has won him the respect of Airbnb’s CEO, Brian Chesky, who increasingly has come to rely on the 53-year-old executive in planning for the company’s future.

The Takeaway

Powered by Deep Research

A litany of Airbnb executives including Tosi have departed over the years, frustrated by their own waning influence or by vacillating company direction. But Lehane has endured. He is now the longest-serving member on the executive team apart from Chesky and his two co-founders, and arguably, after Chesky, the most influential. He has continued to play a central role as Airbnb grapples with the coronavirus pandemic, which did severe damage to the business this spring and is casting a shadow over the company as it heads toward an initial public offering later this fall.

Lehane’s staying power has confounded some current and former colleagues who worked high up in Airbnb. The company had built a hugely successful global brand based on rhetoric about community and trust. Yet here was a top executive who called himself the Master of Disaster, co-wrote a screenplay called “Knife Fight” inspired by his work in politics and wasn’t afraid to plant negative stories about a political opponent. Eight former colleagues said they found him difficult to work with, in part because they took issue with his hardball tactics.

In a statement, Airbnb spokesman Christopher Nulty said the description of the encounter between Lehane and Tosi was “not accurate.”

Policy Machine

The public policy team under Lehane has struggled to counter growing opposition to its expansion in cities with heavy tourist traffic, as residents and local officials have contended the company siphons housing from urban real estate markets, driving up rents.

But Lehane’s defenders say he has succeeded in building a modern media and politics machine within Airbnb. Under Lehane’s watch, Airbnb as a relatively young company managed to blunt some of the most stringent regulations that could have choked off its business in some metropolitan areas. Meanwhile, his proponents say, he brought decisiveness to an executive team that often waffled in big moments.

“He forged a path for what an engaged, active policy team looks like for tech,” said Casey Aden-Wansbury, who reported to Lehane for five years, most recently as Airbnb’s director of federal affairs. She left the company earlier this year and now runs government affairs at grocery delivery firm Instacart. “Nobody had done it before how he did it, in the way he did it. Others are emulating it now.”

Lehane declined to be interviewed for this article, citing the company’s coming IPO. (When The Information first approached Lehane in late August, he replied in an email with an image from the movie “Marathon Man” of Laurence Olivier performing dental torture on Dustin Hoffman.) This article is based on interviews with 40 people who worked with or against Lehane, as well as on his previous conversations with The Information.

Crisis Manager

The pandemic battered Airbnb, sending revenue into a tailspin this spring and forcing the company to lay off a quarter of its staff. But the upheaval played to Lehane’s strengths as a crisis manager. Lehane joined Airbnb in 2015 after a career in politics, government and public relations, including a stint in the White House of President Bill Clinton, fending off accusations of the president’s misbehavior.

As the pandemic moved across the world and shut down travel in March, he circulated a five-page memo on the crisis to his staffers entitled “The Four Phases.” The memo, viewed by The Information, laid out how the company should use the pandemic as a way to burnish Airbnb’s image. The strategy, Lehane wrote, would include “simultaneously playing offense and defense with business and consumer press, including through proactive pitching of stories of how Airbnb is being a responsible actor [and] discreet pitching of recovery stories.”

In the memo, he floated the idea that Chesky should visit a symbolic location, like Wuhan, the epicenter of the Covid outbreak in China, in the fall, to make the case that “travel is critical to belonging and human happiness,” he wrote. The worsening pandemic made the trip idea moot.

But Lehane’s broader strategy seems to be working so far. The last several months of media stories about Airbnb have often focused on the company’s recovery, although concrete data have been scarce.

Lehane’s political training came early. He grew up the oldest of three children in a middle-class family in southern Maine, in a household where policy debates often broke out over dinner. From a young age, Lehane devoured history books and idolized the Boston Celtics. He was named captain of his high school basketball team, despite being only 5 feet 7 inches tall. He would later tell a reporter he was so competitive that he would lock himself in his room if his team lost.

Not long after graduating from Harvard Law School, Lehane landed a job in the White House counsel’s office during President Clinton’s first term, just as scandal was coming to a boil. He penned a memo that outlined a “vast right-wing conspiracy” against the Clintons, a phrase Hillary Clinton later famously used to defend her husband. Lehane proved deft at delivering “counterspin” to the media. “Chris is an aggressive guy, and that’s what was called for,” Joe Lockhart, who became Clinton’s deputy press secretary in 1996, told The Information.

Lehane also disputed early reports that Clinton was having extramarital affairs. At the time, the president was carrying on an affair with intern Monica Lewinsky.

The affair didn’t come to light until 1998. By that time, Lehane had switched jobs and was working as press secretary to Vice President Al Gore, who was preparing a campaign for president. Lehane eventually would join the campaign.

The race famously delivered heartbreak to Democrats when Gore lost narrowly to George W. Bush. Lehane worked briefly for Sen. John Kerry’s presidential campaign in 2003, but quit after unsuccessfully pushing Kerry to take a more aggressive approach against Democratic primary opponents, according to reports at the time. He had one last foray into presidential politics, working for Gen. Wesley Clark’s short-lived White House bid.

Working with Mark Fabiani, his former White House colleague, Lehane built a crisis consulting practice in California. The two men kept their operation lean. “Christopher ran that shop as a one-man band. I’m not sure he had an assistant,” Tom Steyer, a billionaire environmentalist and Lehane’s friend, said in an interview. They racked up clients in need of media corralling, from Goldman Sachs to Lance Armstrong.

In 2014, Lehane started consulting for Airbnb, and he joined full time a year later to oversee both policy and communications, roles that previously had been split. He took over during a potential political quagmire. A referendum was brewing to limit the number of nights Airbnb hosts could rent their homes in San Francisco, the company’s hometown. Airbnb spent $8 million to defeat the measure, winning handily.

Lehane convinced Airbnb executives that it needed to expand its policy and public relations team if the company was going to fend off similar threats elsewhere. The full-time policy staff grew from roughly 15 staffers in 2015 to more than 200 before the coronavirus pandemic hit. Lehane built a separate marketing team focused on political campaigns. The group’s budget overall approached $100 million, a person familiar with the matter said, and the hiring binge and ad blitz created friction with other executives.

The policy chief armed the effort with a cavalcade of former staffers from the administration of President Barack Obama. “At one time we joked that Airbnb was White House West,” said Nick Shapiro, who reported to Lehane as Airbnb’s global head of crisis management from 2015 to 2019 and now runs his own firm, 10th Avenue Consulting.

Lehane’s day-to-day demeanor didn’t necessarily reflect his pitbull reputation. He often tried to keep things loose and inspire young, hungry policy staffers working at their first startup. He diffused his intensity with goofy dad humor and sunny catchphrases. (“I’m a member of the optimist club,” he often tells reporters.) He gave many of his staffers nicknames, often involving sports references, and sent emoji-filled text messages. When he approves a plan of action a staffer emails him, he often just sends a one-word response: “Powerful.”

But some employees were uncomfortable with what they saw as an atmosphere of clubbiness and machismo. He often talked over people in meetings, three former colleagues observed. Another person said Lehane received formal feedback that people wanted him to stop using nicknames and emojis, which he did.

As external pressure on Airbnb has grown, Lehane and Chesky have become close. The two speak often, sometimes on hourslong phone calls. They share a penchant for making grand statements about Airbnb’s role in the world. In early 2018, Chesky wrote a public letter calling on Airbnb to become what he called an “infinite” company. “We think that a company should survive to see the next century, not just the next quarter,” he wrote.

A short time later, Lehane, a history buff, gathered reporters at Airbnb’s headquarters for a presentation about Airbnb’s political progress. He drew parallels between Airbnb’s open platform and the concept of federalism that the U.S. Founding Fathers established in the U.S. Constitution.

The high stakes of Airbnb’s political battles elevated Lehane’s role within the company. Some staffers feared the whole business could come unglued if enough cities decided to strictly enforce zoning laws. The company faced growing opposition from hotel worker unions, which objected to the threat to their business from Airbnb hosts, who, unlike hotels, could operate without licenses or stringent safety rules. Hotel operators joined forces with affordable housing activists and neighborhood groups irritated by noise and parties coming from Airbnb rental properties.

Airbnb fended off some of the most onerous proposals, partly by crafting a message about how short-term rentals inject tax dollars to cities and deliver needed income to individual hosts. Lehane sought to smooth things over with elected officials. Employees would sometimes see him walking big-city U.S. mayors through the company’s glossy San Francisco offices.

Lehane’s job was to cut deals with cities to formalize Airbnb’s business there, even if it meant agreeing to new regulations that could slice into growth. But the rise of full-time, entire-home rentals hosted by real estate professionals—rather than private rooms or homes rented while the owner was on vacation—complicated the narrative that Airbnb was helping individual middle-class homeowners earn a little extra cash.

In some major U.S. cities, including New York, Los Angeles and Chicago, organized labor held significant political sway. Lehane fought the unions aggressively. In 2016, Peter Ward, the New York’s influential hotel union chief, complained to Airbnb executives about Lehane’s tactics, people familiar with the matter said. Lehane’s team at one point gave the New York Daily News the addresses of homes owned by Ward: The newspaper later revealed that the top union boss owned several vacation properties.

“Those are dirty tricks,” Neal Kwatra, a political strategist for the hotel union in New York, told The Information. “They’ve been as negative as you can be.”

The work also put Lehane at philosophical odds with his sister, Erin Lehane, who works in public affairs for the State Building and Construction Trades Council of California, a construction union. She and her brother are close, she said, but they don’t discuss labor issues.

“It’s an area we’re going to have to agree to disagree on,” she said. “Blood is thicker than politics, some of the time.” she said. (Chris Lehane “has repeatedly sought to work with labor,” Nulty, the Airbnb spokesman, said in an email. He cited deals Lehane helped strike at Airbnb with Service Employees International Union and with United Brotherhood of Carpenters and Joiners of America.)

By last year, Airbnb seemed to be losing the public relations war. Some key markets put stricter rules in place, and revenue was roughly flat or declining compared with the previous year in such cities as Tokyo, Berlin, Amsterdam, Copenhagen and San Francisco, according to estimates by AirDNA, which tracks Airbnb’s business.

More trouble could lie ahead. In places including San Francisco, New York and Santa Monica, Calif., the company has settled a string of court cases that have forced the company or its hosts to cut back on the number of rental stays available on its site. In Paris, one of the company’s largest markets, residents may vote soon on new restrictions on Airbnb.

Still, Airbnb’s revenue around the world grew 32% in 2019, financial documents show. Much of the growth in top cities came from Asia, where land-use politics are less intense than in the U.S. and Europe. Nulty said the rules Lehane helped develop in hundreds of cities around the world have created regulatory certainty for the company in the long run.

Since Covid-19 hit, few people have been traveling to cities, favoring small towns or rural areas instead. But Airbnb expects urban travel to resume once the pandemic ends.

In an interview in June, Lehane said he wants to be ready and is trying to use the moment to win back trust from cities. Airbnb recently launched a software tool for local governments to better track short-term rentals. Meanwhile, the company has had to scramble to ban house parties after a number of gatherings at Airbnb rentals turned violent.

“I don’t want this to be misheard—there is nothing good about [the pandemic],” he said in June. “But because people are looking for economic recovery, it is a chance to reset how you’re working with some of these places.”

But as long as the pandemic persists, Lehane said, “everyone in travel, including us, is still an underdog.”

Cory Weinberg is deputy bureau chief responsible for finance coverage at The Information. He covers the business of AI, defense and space, and is based in Los Angeles. He has an MBA from Columbia Business School. He can be found on X @coryweinberg. You can reach him on Signal at +1 (561) 818 3915.