Mad Moms Stigmatized Drunk Driving. Their Next Target: Social Media

A generation ago, a coalition of parents sparked meaningful legislation to combat booze and cars. A new group hopes to accomplish the same thing with social media.

When Andrew Gounardes needed help rallying support for two social media bills he’d introduced in the New York State Senate earlier this year, he knew who to call: Mothers Against Media Addiction.

The New York-based nonprofit parental advocacy group had caught Gounardes’ attention even before it officially launched in March, thanks to its founder, Julie Scelfo, whom a colleague had introduced Gounardes to earlier that year. “It was a match made in heaven,” said Gounardes, a Democrat.

He found a kindred spirit in Scelfo, a former New York Times journalist and mother of three who had founded the group. MAMA, as it’s better known, aims to help parents concerned about the encroachment of smartphones and social media feeds on childhood advocate for policy changes at the local and state level and in schools.

“That’s exactly what our coalition needed in order to build the type of grassroots support to overcome the opposition from tech companies,” said Gounardes. He turned to MAMA repeatedly in the spring to mobilize groups of parents, who would show up in support of his legislation at press conferences, protests and lobbying events at the state capitol.

“They were crucial to our efforts,” recalled Gounardes. “When big tech was going around saying, ‘Don’t regulate us, we know better,’ we deployed parents to say, ‘Uh-uh, you don’t know better, because you’re harming our kids.’”

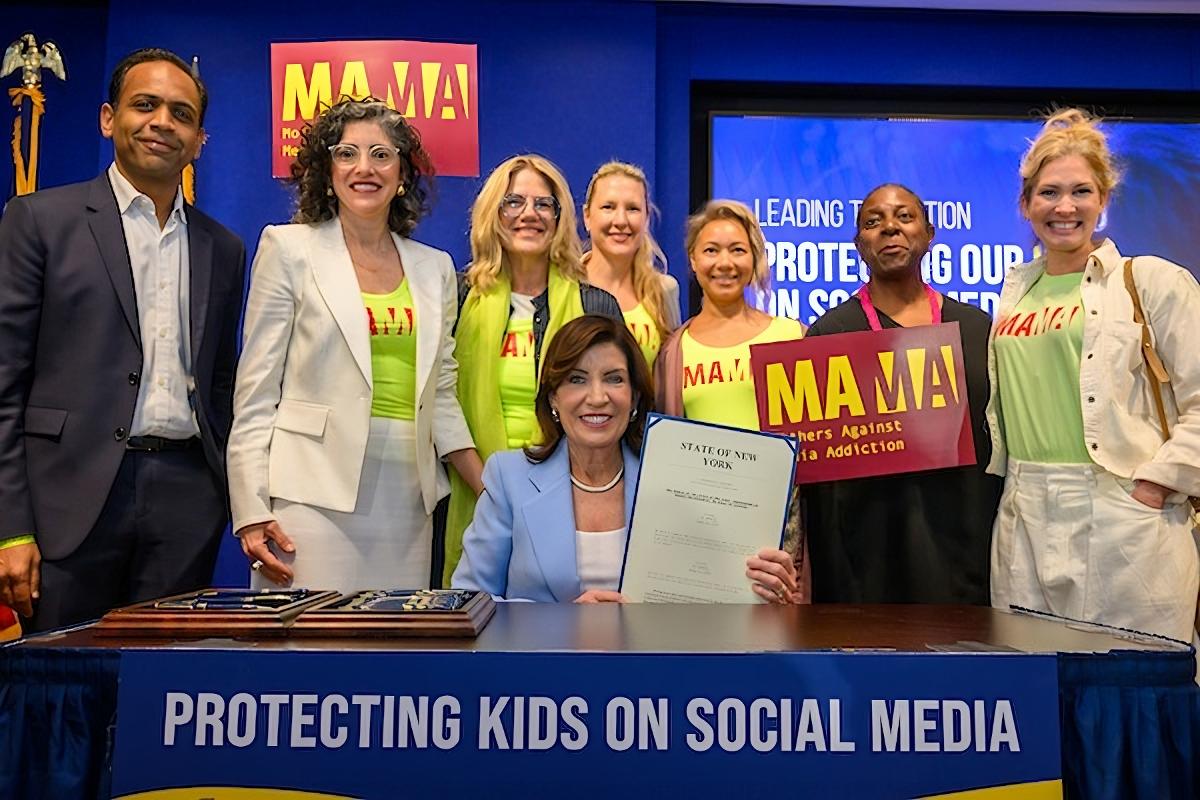

When New York Gov. Kathy Hochul signed the two bills into law in June, Scelfo was seated just a few feet away, surrounded by a gaggle of mothers, clad in highlighter-yellow MAMA shirts and holding signs with sayings like #KidsBeforeTech. It was an early sign of the group’s burgeoning influence.

Angry parents may seem like a cliche, but Scelfo and her group aren’t dilettantes. They’ve pointedly modeled MAMA after Mothers Against Drunk Driving, the influential organization that helped usher in sweeping social and legislative changes over the last century to address the issue of drinking and driving. And MAMA’s goal is to have the same kind of sway over the tech industry.

Over the last six months, MAMA has grown from small meetings in a Brooklyn living room into a nationwide movement, with 19 chapters in 12 states and a lengthy waiting list for opening more chapters. “The demand for MAMA exceeds our capacity to meet it,” said Scelfo, who has received requests to open chapters in two dozen new cities and six countries.

The group’s rapid rise comes at a time of heightened parental anxiety around the potentially harmful effects of screen time and social media use on kids. Jonathan Haidt’s book, “The Anxious Generation,” which argues that the ubiquity of social media and smartphones is to blame for the recent rise in youth mental illness, has been on The New York Times’ bestseller list for the last 28 weeks in a row. (In MAMA’s backyard of New York, there is a 2,200 person waitlist for copies of the book in various formats, per the New York Public Library.)

But the movement goes far beyond books. Over the last two years, social media companies have been hit with a wave of lawsuits filed by parents, schools and state attorneys general; they argue that platforms like Instagram and TikTok have been negligently designed and are addictive to young people, damaging their mental health.

The issue has also managed to bridge the partisan divide in Washington. This summer, a package of child online safety legislation passed the Senate with strong bipartisan support (though its future in the House of Representatives may be bogged down by Republican party infighting). If signed into law, it would be the first comprehensive federal regulation the tech industry has seen in decades.

The movement has its fair share of critics. Sarah Philips, an organizer at digital rights nonprofit Fight for the Future, views parental and legislative efforts to shield children from risqué content online as a misguided and narrow approach to a much broader problem. She described it as akin to an abstinence-only approach to the problem of teenage pregnancy. “It’s politically convenient for legislators to tell parents, like, ‘Oh, well, it’s social media. We need to attack big tech and everything will be solved,’” said Philips. “It’s much more holistic than that, but there’s not a politically expedient answer for the holistic situation.”

Neverless, “parents are hungry for information about what’s really going on with these products,” said Casey Mock, chief policy and public affairs officer at the Center for Humane Technology, a nonprofit that advocates for social media regulations. The group has worked closely with Scelfo since MAMA’s inception, and though it isn’t traditionally a grantmaking organization, it awarded her a six-figure seed grant last year to help with media outreach and opening new chapters.

MAMA meets “a need to overcome the inertia in our state capitals and Congress around a lot of these issues that are due to the insidious influence of the tech lobby,” Mock said.

MAMA’s name and structure harkens back to that of MADD. One of the most successful parent-led political advocacy groups, it helped enact extensive local and national legislation—including a nationwide minimum drinking age, liquor liability laws and sobriety checkpoints—and change public perceptions of getting behind the wheel after drinking.

“It went from being socially acceptable to being socially unacceptable,” said Candace Lightner, who founded the group in 1980 after her 13-year-old daughter was hit and killed by a drunk driver in California.

“The genesis of this movement was in fury and anger,” said Barron Lerner, a New York University professor and medicine historian who wrote a book about the history of drunk driving.

Mothers were outraged that inebriated drivers who harmed or killed their children and other bystanders often received little more than a slap on the wrist from the judicial system. Under Lightner, they banded together and met with lawmakers to demand change.

“The fact that the main figures in the group were mothers and their children had been killed in god-awful stories and they were channeling their grief as mothers into activism so that other mothers, children and loved ones would not be killed was just unbelievably moving for people,” said Lerner. The centering of mothers as the leaders pushing for change on an issue with broad public appeal “gave unbelievable moral authority to MADD.”

Philips, of Fight for the Future, feels it’s “deeply unfair” to compare social media use to drunk driving. “There’s nothing good gleaned from drunk driving…whereas access to the internet and social media does have positives—especially for marginalized kids,” said Philips. “The data shows that young LGBTQ and people of color actually do better…and have better community ties when they have access to online communities.”

Still, Lerner sees parallels between the sociopolitical environments that birthed MADD and MAMA. As with social media in the 2020s, alcohol was a ubiquitous product with a high level of consumption in the 1980s. (Around then, the average American annually consumed nearly 2.8 gallons of alcohol, up from less than 2 gallons after World War II.) This prompted a public health crisis and a MADD-led push for new laws, like an increased legal drinking age across the country.

Lerner thinks America may sit at a similar tipping point with social media—the moment right before a public health crisis actually pushes lawmakers to act.

“We’ve been through a couple decades of this sort of rampant uptake of kids with phones, and there are pros, but…maybe it’s time that the pendulum goes back in the other direction,” he said.

Scelfo agrees. She believes kids today face what she terms a “polycrisis”: At a time when children should be building their social skills and attention span, they are increasingly interacting with the world through a device that she argues can impede the development of both. Parents face immense social pressure to get their kids online—after all, it’s an essential part of modern adulthood and central to many children’s social circles—but struggle to police their activity on personal devices like smartphones, tablets and school-issued laptops.

Part of the problem, Scelfo argues, is that kids are being inundated with content selected by recommendation algorithms. To maximize engagement, the technology can steer impressionable young users toward polarizing content—from videos promoting self-harm to gore and porn.

That can warp kids’ understanding of the world and invite negative social comparisons, she says. At the same time, many social media platforms have been slow to implement safety measures for kid accounts, like prohibiting direct messages from strangers, that Scelfo and other parents see as basic protections.

“We have an entire agency that monitors the safety of air travel. We have multiple bureaus watching over the food supply. And we have a commission working to ensure the safety of consumer products. Why would we exclude social media and other digital platforms from oversight?” said Scelfo.

Like MADD in its early days, MAMA uses a chapter-based structure. Each city has one or more MAMA chapter, led by local parent volunteers. They hold meetings and gather information for the mother ship—MAMA headquarters in Brooklyn—on state policy developments and parental concerns in their community. When someone signs up as a chapter leader, that person agrees to host at least four in-person meetings a year and attend a monthly chapter leadership Zoom meeting.

“MAMA has a three-part mission: It’s parent education, getting phones out of schools and demanding [social media] safeguards. So you don’t become a MAMA chapter leader unless that’s what you’re working towards,” said Scelfo. (She’s been lobbying for a phone ban in schools across the country.)

Jessica Elefante, co-chair of the Brooklyn chapter and a mother of two, has taken special care to keep her meetings informal, even as the subgroup has grown to become MAMA’s largest. Its listserv has around 300 members, and around 50 parents typically attend in-person meetings, which are hosted in backyards and living rooms rather than formal event spaces.

“This should feel kind of like how it felt in the ’90s,” Elefante said.

Attendees nibble on fruit-and-cheese plates and sip wine and nonalcoholic beverages as they trade stories about parenting in a tech world. There’s often a presentation or an educational component. (In true Brooklyn fashion, Elefante once made a zine about curbing your kid’s digital use. One piece of advice: Create a few designated device-free spaces in a home—like the dinner table or the bedroom—so kids get used to unplugging.)

They share details about upcoming protests and rallies, and discuss local awareness efforts, which sometimes take on a guerrilla form, like blanketing the local playground in MAMA postcards or drawing graffiti over Snapchat’s subway ads.

Each meeting, Elefante says, should educate parents on something they didn’t realize was happening—like new research on the effects of social media use on adolescent development—as well as give them a bit of inspiration, and should leave them with marching orders. (At a meeting earlier this year, for instance, Elefante created and shared a pyramid graphic with parents showing the various people in their children’s lives—from government officials to sports coaches to fellow parents—to whom they could talk about how their children use technology when they aren’t around.)

“In these backyards, you’re kind of bringing community back together again,” said Elefante. “And in that community, you get ideas, you get power, you get pissed and you get some gumption.”

Lightner, MADD’s founder, who now advises nonprofits, said that though the chapter model was instrumental to MADD’s success, she usually discourages other organizations from trying to emulate it. “When you’re grassroots and everybody’s full of passion about changing the law and changing attitudes and all that kind of stuff, it’s great,” said Lightner.

But it gets significantly more complicated as the organization scales up and chapters have to adhere to certain business and administrative policies.

The key to making it work starts at the top, says Lightner. “You need a good leader,” she said. “You need a leader that everybody can get along with and work with—not just [activist] groups but politicians too—and they’re rare.”

Scelfo, 50, has long been interested in how media and technology shape society. She studied a mix of sociology and political science as an undergraduate at Barnard College and went on to obtain a master’s degree in media ecology from New York University.

At NYU, she studied with media theorist Neil Postman, whose vociferous criticism of the tech and media industries shaped her thinking. It was a real contrast to how most people were looking at tech in the late ’90s—just as the dot-com bubble inflated to absurd proportions.

Postman, meanwhile, stressed to his students a belief that all technologies are embedded with bias and carry the potential to harm some users while benefiting others. He urged his students to think about how technological change can broadly affect society beyond the technology’s purported use.

That experience molded Scelfo’s worldview and informed her thinking as a parent and her career as a journalist. She worked as a staff writer, first at Newsweek, then at The New York Times, and went freelance after having her third child. Her coverage was varied—one day she’d write about interior design, the next day about a gruesome murder—but her bread and butter was stories about mental health issues, parenting and the experiences of young people.

In 2015, she published a story about a cluster of suicides at the University of Pennsylvania and the intense pressure of perfection felt by young people. “I spent time with students there and found what is now kind of obvious but wasn’t as obvious to the world at that time: what a profound role social media was playing in the lives of adolescents and in their development of their sense of self,” recalled Scelfo. “After reporting that story, I started to get phone calls from parents in my own community and all over the place and connecting the dots.”

She toyed around with the idea of founding a nonprofit organization aimed at addressing these perceived ills but was initially hesitant to focus the group on mothers and children. She worried it could be seen as reinforcing traditional gender roles that she as a staunch feminist didn’t believe in.

“A little part of me dislikes when you hear about mothers having to do something again,” said Scelfo. “It’s like, why is it always moms who have to fix everything?”

She briefly tried to launch a nonprofit with a much broader purview under the name, Get Media Savvy. “We can’t survive this century unless we all have media literacy, but I also knew that that phrase puts people to sleep,” said Scelfo. Ultimately, she concluded that the idea was too broad.

“The idea of focusing on kids and parents was something that we had thought about, but I wasn’t sure that I wanted to be that person,” said Scelfo. “I kept thinking somebody should definitely do that, and I kept waiting for somebody to do it, and nobody was doing it.”

When that didn’t happen, Scelfo relented and founded MAMA. Initially, she didn’t love the name and worried that calling the group Mothers Against Media Addiction could make people feel excluded. One evening in 2023, she asked a stranger she met at a cocktail party—Michael Rourke, a gay dad and CEO of a video production company—for his thoughts on some of the alternative names she was considering, like Parents Against Media Addiction.

“He was, like, ‘No, no, no, no. MAMA is the name. It really is catchy and sticks and it’s powerful,’” Scelfo recalled. “He said, ‘If you do it, I will be your first member.’ I was, like, ‘Do you swear?’”

Rourke said yes, and he now sits on MAMA’s board of directors.

When Elefante, the Brooklyn chapter co-chair, first met Scelfo in September 2023, she was blown away by Scelfo’s story. It was a cool fall afternoon in New York and Elefante was attending a fireside chat about social media at a Chelsea event space featuring Scelfo and Sherry Turkle, a sociologist who has written several books on people’s relationships with technology.

Elefante, a writer and self-described Turkle superfan, had come for the sociologist, but Scelfo quickly wowed her—especially when Elefante heard Scelfo's "voice tremble as she spoke from a mother’s perspective of how angry she was." Elefante remembered thinking, “This is how it changes.”

When the talk ended, she ran backstage and cornered Scelfo. “And I was, like, ‘Whatever you’re doing, I want to help.’”

Today, the Brooklyn chapter she leads has seen such a high level of interest from parents that MAMA has considered opening a second chapter in the borough. (The nonprofit recently launched a Manhattan chapter, which will hold its first meeting at the end of October.)

Most of Scelfo’s time these days is spent fundraising in the hopes that MAMA can soon expand its paid staff, which currently numbers around a dozen part-time employees. That optimism was on full display at an inaugural benefit event the group held recently in Brooklyn to raise donations and celebrate six months of “action in defense of childhood.”

On a chilly late September evening, about 200 parents and allies packed into a swanky event space in the Gowanus neighborhood of Brooklyn to sip cocktails with names like “Mama’s Helper” and “Papa’s Deep Breath” while a live band played Prohibition-era jazz.

Parents traded war stories of teenage tech battles and small victories as MAMA organizers, clad in the group’s signature yellow trucker hats sporting the group’s logo, flitted around the space, preparing for the evening’s main programming, a series of talks from parents and community leaders.

When the time came for the event to begin and guests began to migrate to their seats, a small problem emerged: They hadn’t anticipated this much interest. The venue’s 130-some chairs quickly filled up, leaving standing room only. Undeterred, dozens more packed into the room.

Paris Martineau (@parismartineau) is a feature writer and investigative reporter for The Information's Weekend section. Have a tip? Using a non-work device, contact her via Signal at +1 (267) 797-8655.